Conceived in Liberty or Conceived in Sin? Exploitation and Modern Prosperity

The difference is hard to appreciate. Our world is very different from our ancestors’, and our lives are inconceivably good in just about every way. Sometimes we use our liberty and prosperity to live like pigs, it’s true, but for the most part, we do a good-enough job that the planet can support eight billion people at steadily rising living standards with a lot more on the way.

As Deirdre McCloskey and I argue in our book Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich: How the Bourgeois Deal Enriched the World,1 it happened because we embraced the Bourgeois Deal: liberty and dignity for innovators and entrepreneurs who want to try new things. We started leaving them alone (sort of) and even started encouraging them (sort of), and they made us rich: as the economist William Nordhaus estimates, 98% of the value of innovation has accrued not to the innovators but to consumers.

In the Beginning, Things Were Awful

As Thomas Hobbes wrote, life in the state of nature was solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short, even though our ancient ancestors had more natural resources per capita than we do and didn’t have to deal with pollution, climate change, factory farming, and other problems of our modern industrial society.

Consider this uplifting statement from 1993 Nobel Laureate Douglass C. North’s 2005 book Understanding the Process of Economic Change:

- Economic history is a depressing tale of miscalculation leading to famine, starvation, defeat in warfare, economic stagnation and decline, and indeed the disappearance of entire civilizations.

It is a pretty apt description of all history. But something wonderful happened: beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century; our clumsy species embarked on a Great Enrichment that fundamentally changed how we live.

First, there are a lot more of us. The world went from having almost nobody to having a population in the neighborhood of eight billion. Second, we live a lot longer. Third, we have much higher standards of living because we produce a lot more stuff: far, far more finished goods and services than our ancestors did, and it keeps growing yearly. Fourth, improvements on almost every margin mean we have greater human scope for lives well-lived.

Now We Are R.I.C.H.

We are R.I.C.H.: Rich, Interconnected, Civilized, and Healthy. What does this mean?

First, I’m referring to those of us lucky enough to have won the geographical and historical lottery and who find ourselves in European countries or their offshoots like the United States and Canada. If you’re reading this, there’s a very good chance you’re among the richest 5% of people on earth and the richest 1% of people who have ever lived.

We’re also Interconnected. Most of our ancestors went their whole lives without seeing someone who didn’t look, talk, or pray the way they did—and when they did, they were probably trying to kill one another at the behest of a chief, warlord, or noble. In today’s commercial society, we get to enjoy the best that every civilization has ever created, and we can do it with devices that make it possible to maintain running conversations with friends and family members (and adversaries!) around the globe.

We’re Civilized. The surviving records we have suggest that a lot of our ancestors didn’t leave behind much more than a body count. Today, we’re able to guard ourselves against the elements. People today don’t slaughter each other with anything like the frequency their ancestors did. We create and enjoy art, literature, and music. We contemplate our existence, and to borrow from Johannes Kepler, we think God’s thoughts after him in the laboratory or while constructing mathematical models.

We’re also Healthy. Today’s leading killers are diseases of old age and affluence like cancer, not pathogens or warfare. More people die of cancer because more people live long enough to get cancer. With every passing year, the heartbreaking spectacle of parents having to bury their own children becomes progressively less and less a part of the human experience.

What was the major mover? As Deirdre McCloskey and I argue, it happened because we embraced the Bourgeois Deal rather than the Blue Blood Deal, the Bureaucratic Deal, the Bolshevik Deal, or the Bismarckian Deal. It was economic liberty and social dignity for entrepreneurs and innovators, what McCloskey has called “equality of permission.” We left them alone, and they made us rich.

We’re Not R.I.C.H. Because We Did S.I.C.K. Stuff

A steady stream of books and articles perhaps most notably summarized in the New York Times 1619 Project attributes modern economic growth to a S.I.C.K. legacy: Slavery, Imperialism, Colonialism, and Knavery. A growing literature on the “New History of Capitalism” argues specifically that slave-grown cotton fueled and financed the Industrial Revolution. Here’s what Karl Marx wrote in The Poverty of Philosophy2:

- Direct slavery is just as much the pivot of bourgeois industry as machinery, credits, etc. Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry. It is slavery that gave the colonies their value; it is the colonies that created world trade, and it is world trade that is the precondition of large-scale industry.

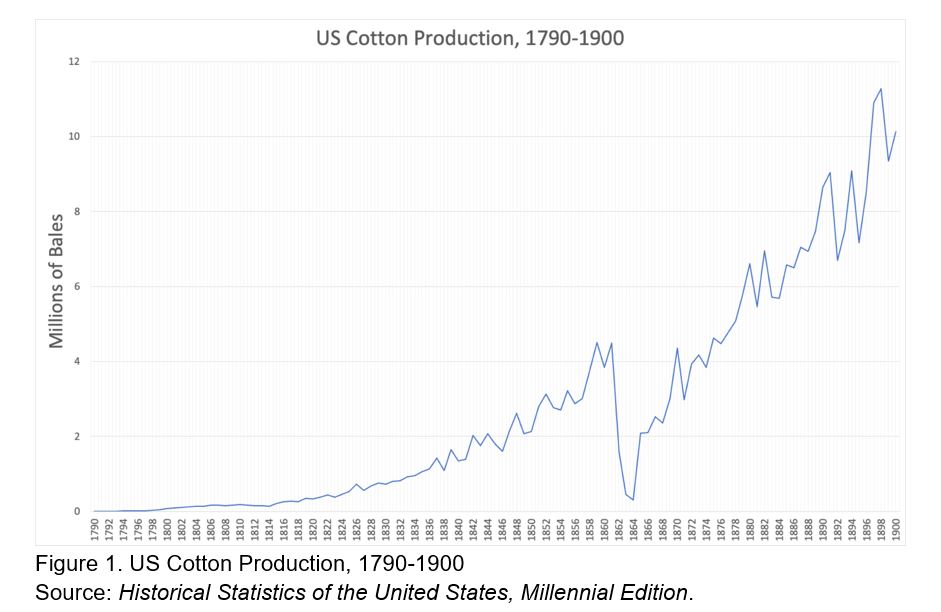

Nineteenth-century data do not support the thesis that slavery was in any way “necessary” for U.S. cotton production, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Source: Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition

There was a huge dip in cotton production during the Civil War as the South actually turned its guns inward and thought it would bring the world to its knees and draw Britain and France into the war on their side by starving the world of the cotton it so desperately needed. That, it turned out, was a serious miscalculation. As it happened, there were a lot of substitutes for Southern, slave-produced cotton, namely, cotton produced in Egypt, India, and elsewhere. Britain started importing cotton from other sources, and the market solved the problem Confederate King Cottoners tried to create. Cotton production rebounded quickly after the war and emancipation, which suggests that Marx was wrong to write, “without slavery you have no cotton.” Within about half a decade after the end of the war, U.S. cotton production was where it had been before the war.

Slavery, of course, is one of the oldest and most ubiquitous human institutions. If slavery per se could have caused a Great Enrichment, it would have happened a long time ago, somewhere else where slavery and long-distance slave trades thrived, as they did across the Sahara Desert and around the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, even if we restrict our attention to the Atlantic trade, the Great Enrichment would have happened in Portugal and Brazil rather than England and the United States if slavery itself could cause industrialization.

Imperialism and colonialism are also popular explanations. As Niall Ferguson has argued, however, imperialism was the least-original thing Europeans did after 1492. If conquest leads to industrialization, then once again, it would have happened somewhere else long before it actually did.

Knavery and exploitation are curses, not blessings. The world—even the rich world—is poorer today because of slavery, not richer. We would be better off had slavery disappeared and had the former slaves and their descendants been integrated into a free market economy. We would have saved a lot of blood and treasure had our ancestors gotten rich by producing and trading rather than taking and raiding.

How People Solve Problems in Free Markets

So how did the Great Enrichment happen? People got rich because we embraced innovation and unshackled what Julian Simon called The Ultimate Resource: the human mind. We would have gotten even richer had we unshackled even more minds. The marketplace is the social sphere in which strangers cooperate for mutual advantage, and when we simply leave people alone, they prove themselves remarkably adept at solving problems in ways outside observers never would have considered. We see examples in sectors too many people think are “too important to be left to the market” like food, water, health care, education, and housing.

Food and Water. Few things are as important as food and water: without them, you will die. You’ve probably seen a yard sign somewhere listing the tenets of a woke catechism that includes a phrase like “water is life.” The relevant question, though, isn’t, “should we have water or not?” but, “should we have a little more water or a little less?” Another question is “what should we do with the next unit of water?” We might drink it. We might bathe with it. We might put it in a balloon and throw it at a friend. Regardless, since we don’t produce and allocate it according to market prices, we’re wasting lots of it. The economist David Zetland has a lot more to say on this: to the extent that the world has a “water problem,” it’s that water is not privately owned and traded in free markets.

Since we don’t let prices rule in the market for water, we end up creating a lot of problems. We turn neighbors into enemies and effectively deputize them as spies when we make rules saying things like “even numbered houses can water on these days, and odd numbered houses can water on those days,” instead of just pricing water. Prices give people the incentives and transmit the information they need in order to choose wisely, and there are lots of easy ways we could expect people to conserve water if we got the prices right. Maybe we’d take shorter showers or have fewer water balloon flights or leave the Slip-n-Slide in the garage. There are a lot of ways people adjust.

“Food is too important to be left to the market” has been used to justify all sorts of things like tariffs on foreign produce and farm subsidies. In both cases, we’re worse off. Tariffs passed in the name of “food security” or “American jobs” make us worse off. They encourage us to waste resources producing things domestically when they could be had for lower prices from abroad. They also reduce the amount of whatever is being “protected” that Americans get to enjoy. It’s a raw deal.

Consider farm subsidies and price supports. Just like you get too little of something when you tax it, you get too much of something when you subsidize it. If farmers produce a lot of corn and soybeans they wouldn’t have produced without a government subsidy, they’re wasting resources. The necessary labor, capital, and other resources would produce something more valuable if they weren’t wasted growing corn and soybeans. “Too important to be left to the market?” Hardly.

You’ve probably also heard that housing is a human right that is “too important to be left to the market” because greedy landlords, investors, and developers won’t build enough and will charge too much. Housing isn’t expensive because landlords and developers are unusually greedy. It’s expensive because new housing construction in places where it is most desperately needed (like San Francisco, Boston, and New York) is more expensive because of regulatory red tape. Trying to fix it with rent control makes it worse by creating shortages. In this case, the problem isn’t that we’re not doing enough to help the poor. It’s that we have a lot of policies in place that actively harm them.

Healthcare. The argument for government intervention in the market for health care is a bit more plausible because diseases can be transmitted. This doesn’t mean it’s too important to be left to the market, and the bureaucratic nightmare that is the American health care system is a pretty direct result of failing to leave it to the market. Occupational licensing makes health care a lot more expensive, and third-party payer systems and layers and layers of opaque regulation make it harder for people to compare the costs and the benefits of different treatment options. People recoil at the idea of relaxing licensing requirements because it will reduce the quality of professional care. It will increase the total amount of care, however, by making it easier for people to fill the gaps in the market between “grandma’s home remedies and rubbing some dirt on it” and specialized high-quality care.

Education. This is one of my favorites. Education supposedly has spillover benefits, which as most economists will tell you might make a case for government subsidies to education, but it doesn’t make a case for government provision of education. And that, of course, is to say nothing about who gets to define “education.” I’m kind of shocked at the audacity of people claiming that parents don’t have any reasonable say in what gets taught or how students are educated. It seems undemocratic.

Leave People Alone, and They Will Make Us Rich

People are very resourceful, and they can probably figure out food, water, housing, health care, education, and all sorts of other things without centralized control. One of the problems, of course, is that we don’t know exactly how people will adjust to their new incentives, but we have a pretty good reason to think they can as long as we embrace the Bourgeois Deal.

This, of course, raises a difficult question. If the Bourgeois Deal is so great, why isn’t it more popular? Why don’t more people take the time to learn a thing or two about economics? For this, I want to turn to my favorite economist, Thomas Sowell.

For more on these topics, see

- “Why We Don’t Need a ‘New’ History of Capitalism,” by Phillip Magness, et al. Online Library of Liberty, Liberty Matters, October 5, 2023.

David Zetland on Water. EconTalk.

David Zetland on Water. EconTalk. Why Housing Is Artificially Expensive and What Can Be Done About It (with Bryan Caplan). EconTalk.

Why Housing Is Artificially Expensive and What Can Be Done About It (with Bryan Caplan). EconTalk.

I wanted to be like Thomas Sowell when I grow up. In addition to being, I believe, the clearest communicator of economic ideas on the planet, he’s a bona fide expert on Karl Marx and Marx’s intellectual legacy. Or rather, as Sowell puts it, his anti-intellectual legacy. In his book Marxism: Philosophy and Economics, Sowell writes,

- Much of the intellectual legacy of Marx is an anti-intellectual legacy. It has been said that you cannot refute a sneer. Marxism has taught many–inside and outside its ranks–to sneer at capitalism, at inconvenient facts or contrary interpretations, and thus to sneer at the intellectual process itself.

That, unfortunately, is what we’re still up against. Fortunately, some still smile rather than sneer at the intellectual process itself. Those places are making us rich, and they give me a lot of hope for the future.

Footnotes

[1] Art Carden, Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich. EconLog, Liberty Fund Economics Book Club, March 24, 2022.

[2] The Poverty of Philosophy: Answer to the Philosophy of Poverty, by M. Proudhon. Marxists.org.

*Art Carden is Margaret Gage Bush Distinguished Professor of Economics and Medical Properties Trust Fellow at Samford University in Birmingham, AL and a Research Fellow with numerous organizations.

Author’s Note: This article is adapted from a presentation titled “Conceived in Liberty or Conceived in Sin? Exploitation and Modern Prosperity” at the Club for Growth Foundation’s 2022 Fellowship Seminar in Nashville, TN, May 20, 2022. I gave a talk closely related to this one at Northwood University in April 2022, which you can watch at Art Carden–Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich: How the Bourgeois Deal Enriched the World–2022 on YouTube.

For more articles by Art Carden, see the Archive.

The post Conceived in Liberty or Conceived in Sin? Exploitation and Modern Prosperity appeared first on Econlib.