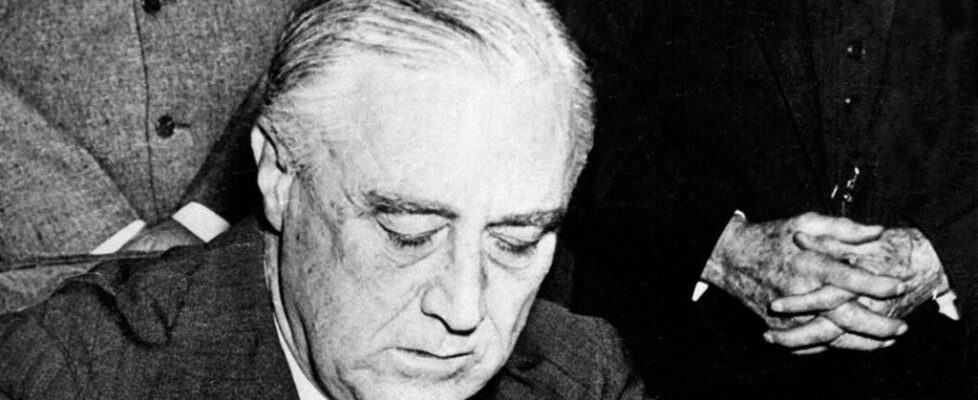

How FDR Built the the American Security State

New Deal Law and Order: How the War on Crime Built the Modern Liberal State, by Anthony Gregory, Harvard University Press, 512 pages, $45

The United States is notorious both for mass incarceration and for militarized police forces. The U.S. Border Patrol lends unmanned drones to police around the country, who use them to surveil ordinary citizens. Intergovernmental task forces and fusion centers coordinate cooperation among law enforcement officers at all levels of government. Years after COINTELPRO, the FBI is still spying on dissenters. The United States professes a commitment to liberal values, individual rights, and equal protection, but it combines this rhetoric with a muscular security state.

How did we get here? Many focus on the ways Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton escalated federal police power. But in his new book, New Deal Law and Order: How the War on Crime Built the Modern Liberal State, historian Anthony Gregory emphasizes how an earlier president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, built up policing, incarceration, and the modern security state. Liberalism, Gregory shows, can be used to build an apparatus of repression.

To set the stage, Gregory explores a series of struggles over both real and perceived “lawlessness” in the period from the Civil War through the beginning of the Great Depression. This included the lawlessness of white Southerners who engaged in racial terror and lynching. It also included labor unrest, where both the actions of strikers and the actions of strikebreaking private security forces were frequently framed as lawless. It included bank robberies and gang violence. It included the Prohibition-fueled growth of organized crime. It included kidnappings and human trafficking across state lines.

In America’s federalist system, designating all these problems as “lawlessness” rather than merely “crime” served an important function. Ordinary crimes were understood as problems for local and state authorities. The notion of “lawlessness” was used to argue these were national problems that called for federal intervention. Yet attempts to create a nationwide basis for enforcing law and order all failed until Roosevelt built a durable nationwide apparatus of crime control—an apparatus quickly used for repression as well.

To do this, officials such as Attorney General Homer Cummings worked with state and local governments, offering incentives to expand policing and incarceration in line with the administration’s goals. Gregory calls this mutually beneficial arrangement among state, local, and federal officials to expand their power “war-on-crime federalism.”

Roosevelt and his allies engaged in a trickier sort of coalition building among diametrically opposed ideological factions. White supremacist Southern Democrats got federal support for their local police, while civil rights activists hoped federal officials would use their new powers to stop lynchings. The administration largely refused to do the latter, but officials walked a fine line that allowed them to keep the anti-racists in their coalition: Some Democrats sponsored unsuccessful anti-lynching legislation, Roosevelt occasionally spoke against lynching, and he met with anti-lynching activists.

Another way Roosevelt maintained a broad coalition was to retain top officials from previous administrations and help them expand their power. Harry Anslinger, who became head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics under Roosevelt’s Republican predecessor, remained in that position; he used Roosevelt’s war on crime to build the modern war on drugs. Similarly, J. Edgar Hoover had led the Bureau of Investigation under multiple GOP presidents. While some close to Roosevelt wanted to remove him, the attorney general kept him on, and Hoover ended up playing an instrumental role in the new war on crime. In the process, Hoover expanded his agency’s power, eventually transforming it into the Federal Bureau of Investigation. His agents took on many roles during Roosevelt’s administration, including surveilling the president’s political opponents.

The war on crime also helped Roosevelt redefine liberalism in a manner that allowed a more expansive role for coercive, repressive state action. Although some libertarians and other classical liberals might want to deny Roosevelt the title of liberal, this book makes a persuasive case that liberal ideals and rhetoric played a crucial role in legitimizing the president’s war on crime and holding together the coalition that supported it, just as it did for his broader package of New Deal reforms.

Even some who initially criticized the Roosevelt administration’s consolidation of power, such as Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union, eventually praised his administration. When Roosevelt was using the security state to repress those who stood in the way of U.S. mobilization for World War II, Baldwin said “prophets who foretold the collapse of democratic liberties…have been confounded by the extraordinary record of war-time freedom.” While Baldwin recognized Japanese internment as a gross and unnecessary violation of civil liberties, he called it a “blot” on Roosevelt’s “record of general sanity and tolerance.” Baldwin held off on releasing a report about Hoover’s use of the FBI to repress dissent because he considered Hoover a lesser evil compared to the conservative Texas Democrat Martin Dies Jr., who led the House Un-American Activities Committee. Baldwin took to describing civil liberties abuses by the new security state as exceptions that marred the agencies’ otherwise admirable record of respecting the rule of law.

This angle is one of the most valuable things about Gregory’s book: It shows how appeals to liberal values and ideals can be used to empower brutal coercion and repression. While all states enact violence, they administer this violence through the cooperation of many people inside and outside the formal government. To secure this cooperation, they rely on ideas and rhetoric. Even the ideas and rhetoric that libertarians love can be turned into justifications for violent state-building exercises.

In Roosevelt’s case, those state-building exercises included gun control; the drug war; increased cooperation between federal, state, and local law enforcement; expansion of incarceration; and growing links between domestic police and the national security state. The New Deal war on crime created a coercive apparatus that Roosevelt used throughout World War II to maintain wartime regimentation and discipline, including such shameful civil liberties abuses as Japanese internment.

New Deal Law and Order alsoillustrates how seemingly disparate forms of state power are mutually reinforcing. Efforts to expand welfare or provide public services were deeply entangled with the New Deal war on crime. The Tennessee Valley Authority, for instance, did not simply expand public services, aid rural electrification, and help modernize the American South. It also required security officers to protect its facilities. More broadly, crime-fighting strategies often emphasized both repression and prevention, with prevention proposals tied to public services. The growth of the welfare state thus reinforced the growth of the security state. Meanwhile, as the security state grew for domestic law enforcement purposes, it self-consciously learned from past foreign conflicts—and then built connections between policing and national security during World War II.

Over time, these connections have militarized law enforcement at all levels of government. When a local police department carries out a SWAT raid, seizes property through civil asset forfeiture, or uses a drone to surveil a protest, it is often using tools it received from Washington. We’re still living in a world of “war-on-crime federalism,” and Gregory’s work is indispensable for understanding how we got here.

NATHAN P. GOODMAN is a senior fellow in the F.A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center. His research focuses on public choice, institutions, self-governance, defense and peace economics, and border militarization.

The post How FDR Built the the American Security State appeared first on Reason.com.