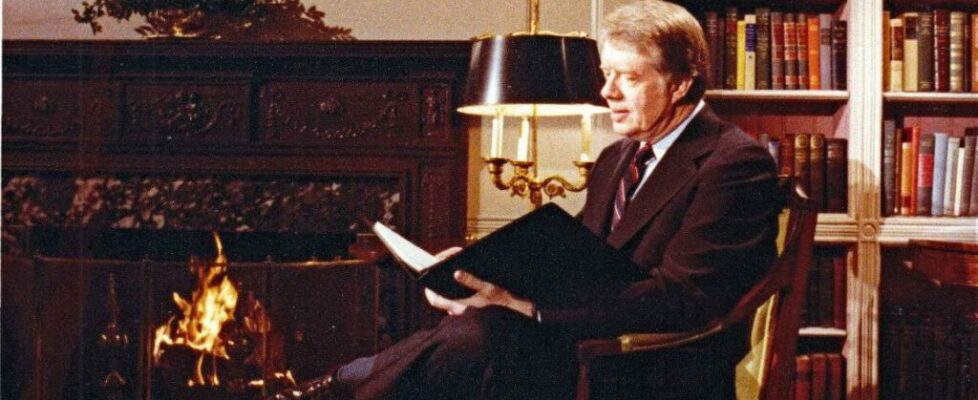

RIP Jimmy Carter, the ‘Passionless’ President

James Earl Carter, the 39th president of the United States, passed away Sunday at 100 years old.

American presidents are guaranteed at least two honeymoons: when they assume office, and when they assume room temperature. We typically send them off with embarrassing solemnity and reverence. Even Dick Nixon got a “national day of mourning,” while Jerry Ford—who only pardoned the bastard—got five days of ceremonies plus a full state funeral after a stop at the Abraham Lincoln Catafalque.

In the coming weeks, we can expect to hear a lot of nice things about how “our best ex-president” hammered nails for Habitat for Humanity instead of racking up $200,000 speaking fees from Goldman Sachs. But even the most effusive Democrats will likely stop short of praising Carter’s performance as president, while those Republicans able to maintain a dignified silence will bide their time until it’s OK to start burning him in effigy again.

Whatever ceremonial respect Jimmy Carter gets paid while he’s lying in state, it’s unlikely to change his historical reputation as a second-rater. The scholars who fill out the presidential rankings scorecards typically dump him in the bottom half of American chief executives, and most of the rest of America remembers him as a colossal failure.

There’s something in the Carter presidency for just about everyone to deplore. If Barack Obama was “like a Rorschach test“—people saw in him what they wanted to see—then Jimmy Carter evokes images we’d rather blot out: gas lines, yellow ribbons around trees, burning helicopters in the desert, that goddamned cardigan sweater. He left office as “a potent symbol for the futility of government and naïveté of reformist zeal,” historian Bruce J. Schulman writes, “as much a relic of the despised, disparaged ’70s as yellow smiley faces, disco records, and leisure suits.”

Conservatives remember the man as a sanctimonious scold and serial appeaser, their go-to rhetorical shorthand for an America that just doesn’t win anymore. For liberals, he was an embarrassment: a micromanaging bumpkin, woefully lacking in “the vision thing.” E.J. Dionne called him “liberalism’s great lost opportunity,” and in a May 1979 Atlantic cover story, “The Passionless Presidency,” former Carter speechwriter James Fallows carped that his old boss “has not given us an idea to follow” and “fails to project a vision larger than the problem he is tackling at the moment.”

True enough. The Carter presidency was short on transformational zeal: It brought forth no New Deals, no new frontiers, no major wars—not even a splendid little one. Jimmy Carter never lit a “fire in the minds of men.” He hardly managed to convey a sense that he knew what the hell he was doing. But his narrow focus on the problems of the moment made significant improvements in American life.

In an era of strongman politics, when the presidency has become the focal point of all too much passion, there’s a lot to be said for James Earl Carter’s comparatively modest conception of the office. At home, our 39th president left a legacy of workaday reforms, paving the way for the “Reagan boom” by taming inflation and serially deregulating air travel, trucking, railroads, and energy. Abroad, he favored diplomacy over war, garnering the least bloody record of any post–World War II president. So what if he didn’t look tough, or even particularly competent, as he did it? A clear-eyed look at the Carter record reveals something surprising: This bumbling, brittle, unloveable man was, by the standards that ought to matter, our best modern president.

‘He Is Not a Democrat’

A pathological “can-do” spirit has become practically mandatory for modern chief executives. Barack Obama took office pledging to slow the oceans’ rise and bend the very “arc of history”; Donald Trump vowed, somewhat less lyrically, “I will give you everything… I’m the only one.” “We can deliver racial justice,” Joe Biden declared in his inaugural address, and by the time of his second State of the Union earlier this year, he’d added, “Let’s end cancer as we know it” to the presidential punch list: “We are the United States of America, and there is nothing, nothing beyond our capacity if we do it together.”

Yet, Jimmy Carter’s admirably brief inaugural struck a note of programmatic humility: “Even our great Nation has its recognized limits….We can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems. We cannot afford to do everything….We must simply do our best.”

The miserly scale of Carter’s ambitions drove Arthur Schlesinger Jr., dean of the liberal historians, to near apoplexy in the pages of The New Republic. Quoting Carter’s second State of the Union, Schlesinger railed: “Let him speak for himself: ‘Government cannot solve our problems. It can’t set the goals. It cannot define our vision. Government cannot eliminate poverty, or provide a bountiful economy,…or save our cities’….Can anyone imagine Franklin D, Roosevelt…Harry Truman, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, or George McGovern uttering those words?” Carter “is not a Democrat,” Schlesinger spat, “at least in anything more recent than the Grover Cleveland sense of the word.”

Cleveland, “Rand Paul’s favorite Democratic president,” believed that “when a man in office lays out a dollar in extravagance, he acts immorally by the people”—and he racked up a record number of spending-bill vetoes accordingly. By those standards, Jimmy Carter’s fiscal conservatism falls far short. After all, the guy gave us two new cabinet departments, Education and Energy. (Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush only managed one each.)

But grading on a 20th century curve, Schlesinger was on to something.

Carter’s attitude toward government extravagance permeates the contemporaneous diary he kept during his presidency. In it, he sounds more like a penny-pinching Gradgrind than a tax-and-spend liberal—complaining that partisans of the B-1 bomber are “conveniently forgetting there is such a thing as a cruise missile,” harrumphing that “it’s obvious that the space shuttle is just a contrivance to keep NASA alive,” and, on Social Security, railing against a Congress that’s “almost spineless when considering extra benefits for special interest groups, in this case retired people.”

Presidential diaries are self-serving documents, but Carter’s seems unlikely to have been bowdlerized for public consumption, given the level of oversharing: “DECEMBER 20 [1978]: I had a horrible attack of hemorrhoids, but I couldn’t stop working because I had to prepare all the directives for Cy for the SALT and the Mideast negotiations.” (It took a Christmas miracle to end his suffering: “DECEMBER 31: On Christmas Day the Egyptians prayed that my hemorrhoids would be cured because I was a good man, and the following day they were cured.”)

Besides, what’s in Carter’s diary is backed up by his performance in office, where he repeatedly stood up to free-spending Democratic majorities in Congress to hold the line on the budget. His record on nonmilitary spending was better than the five presidents who preceded him—dramatically so in some cases. (He ran up the tab less than half as much as Richard Nixon.) And Carter was the only post-war Democratic president to put the brakes on the push for national health care, spurring a damaging primary challenge from Sen. Ted Kennedy (D–Mass.) in 1980.

On the campaign trail in 1976, irked at criticism from the liberal dreamboat, Carter let fly with “I’m glad I don’t have to kiss Teddy Kennedy’s ass to win the nomination,” a quote that made the front page of The Atlanta Journal. As president, Carter’s refusal to buss the Kennedy fundament brought the two camps to open warfare over the senator’s plan for comprehensive health insurance. “Kennedy’s proposals would be excessively expensive and impossible to pass,” Carter wrote, “it’s almost impossible for me to understand what he talks about….He wants a mandatory collection of wages from everyone to finance the health program.”

If “Democrats had elected a Carter instead of an Obama” in 2008, notes the Cato health policy scholar Michael Cannon, “there would be no Obamacare.”

Stumbling Toward Sound Money

In health care and elsewhere, the key motivation behind Carter’s relative parsimony was the need to fight the greatest economic threat of the late 1970s: roiling inflation. Massive spending on the Vietnam War and the Great Society “were accommodated by easy monetary policy and rising inflation,” Harvard’s Jeffrey Frankel explains. Fed Chairman “Arthur Burns gunned the money supply in 1972, evidently in order to ensure [Nixon]’s re-election, while wage-price controls—supposedly anathema to conservatives—kept inflation temporarily under control. Of course inflation soon re-emerged more virulent than ever.”

Carter didn’t have a good grasp of the problem’s underlying causes. “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” Milton Friedman observed in 1963. But Carter’s theory was a sort of Bizarro World Friedmanism where prices spiraled as a result of acquisitiveness and lack of public spirit. For the 39th president, inflation was always and everywhere a moral phenomenon.

On October 24, 1978, with the rate pushing 9 percent, Carter went on television to announce his Anti-Inflation Program in a characteristically hectoring, schoolmarmy tone. His voluntary wage and price targets were “a standard for everyone to follow—everyone,” and don’t you dare make fun: If you “ridicule them, ignore them, pick them apart before they have a chance to work, then you will have reduced their chance of succeeding.”

Still, the rest of the speech outlined a program free marketeers and fiscal conservatives could get behind: “We will cut the budget deficit…slash Federal hiring…remove needless regulations [and] use Federal policy to encourage more competition,” he proclaimed. Carter also flatly rebuffed calls for wage and price controls as inconsistent with “our free economic system.” Nixon’s 1971 wage and price freeze was an economic folly but a political success, enjoying massive public support. A renewed effort might have been popular again—a May 1979 Gallup poll showed the public in favor, 57–31 percent—yet Carter never pushed Congress to grant him that authority.

Instead, in August ’79, he appointed inflation hawk Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve, with the brief of tightening the money supply. Volcker promptly did exactly that, at great political cost to Carter’s reelection prospects. “I called Paul Volcker, who is raising the discount rate,” Carter writes in his diary entry for September 25, 1980. “This will hurt us politically, but I think it’s the right thing to do.”

‘The Great Deregulator’

“Of all our weapons against inflation, competition is the most powerful,” Carter insisted in 1978. That view spurred him on toward his most impressive domestic achievement. For loosening controls on oil, railroads, trucking, and airlines, he should, as libertarian writer Daniel Bier suggests, be remembered as “the Great Deregulator.”

If instead, he’s remembered more as a censorious meddler, Carter himself bears much of the blame. This, after all, was the president who spent a nationally televised address hectoring Americans to “park your car one extra day per week” and “set your thermostats to save fuel.” Popularly known as the “Malaise Speech,” though the word malaise didn’t actually appear in it, that July 15, 1979, address bemoaned a “crisis of confidence…strik[ing] at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will.”

Amid half-baked pop-philosophical musings about conspicuous consumption and “our longing for meaning,” Carter laid out a policy agenda aimed at solving the ongoing energy crisis. “All the legislation in the world can’t fix what’s wrong with America,” he averred. Still, he seemed determined to give it a try, with an “energy security corporation” devoted to the promotion of “gasohol,” solar power, and other alternative fuels; import quotas on foreign oil; and a windfall profits tax that would undermine the stated goal of more domestic production.

The president blamed the gas lines on “excessive dependence” on the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and foreign oil. Actually, as Carter’s own energy secretary, James Schlesinger, admitted: “There would be no lines if there were no price and allocation controls.” Here again, Carter managed to stumble toward the correct solution, signing a bill removing regulatory barriers to a national market in natural gas and then, via administrative action, removing most price controls on oil.

On transportation deregulation, Carter moved with far greater confidence and clarity. He knew what he was doing when he picked Alfred Kahn to head up the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) in 1977. Kahn, an academic economist with formidable political skills, had previously told Congress that transportation was “the leading example” of an area where “something close to complete deregulation is long overdue.” The CAB had used its authority over routes and pricing to squelch competition and keep fares artificially high: From 1950 to 1974, it rejected all 79 applications it received from companies looking to provide domestic service.

Kahn proved an inspired choice. As CAB head, his philosophy was “we’ll do what we can, until somebody says we can’t”—enabling price competition via “supersaver” fares and approving the entry of any airline capable of providing service. When Kahn’s friend Irwin Stelzer, an economist, complained about a flight where he had to sit next to “a hippie, who obviously hadn’t bathed in months and undoubtedly paid a much lower fare,” Kahn retorted that “we are waiting to hear from the hippie” before taking any action.

By lobbying for, and signing, the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, Carter ensured that what Kahn had put in motion couldn’t be reversed by future regulators. The law phased out the CAB’s authority to restrict market entry and prices, and the agency closed up shop entirely by the end of 1984.

Turning to trucking and rail, where the Interstate Commerce Commission’s stranglehold over competition had been equally stifling, the Carter team moved just as swiftly to lift controls. Despite fierce opposition from the Teamsters—and an attempt to bribe a key senator—Carter pushed hard for deregulation, threatening to veto any measure that fell short. In July 1980, he signed the Motor Carrier Act, which removed most restrictions on the goods truckers could carry, the routes they could serve, and the fees they could charge. In October of that year, in the midst of a wave of railroad bankruptcies and calls for nationalization, he signed the Staggers Rail Act, substantially deregulating the freight rail industry. As The Wall Street Journal‘s Holman Jenkins recalled in a 2009 column, “When the bill stalled, a hundred phone calls went from the White House to congressmen, including 10 by Mr. Carter in a single evening.”

Upon signing the Staggers bill, Carter took a victory lap, calling it “the capstone of my own efforts to get rid of needless and burdensome Federal regulations which benefit nobody and which harm all of us….We deregulated the airlines, we deregulated the trucking industry, we deregulated financial institutions, we decontrolled oil and natural gas prices, and we negotiated lower trade barriers throughout the world for our exports.” Along the way, this observant Southern Baptist—a president you’d never want to have a beer with—even signed a bill to legalize home brewing.

We should “puzzle more deeply over the Carter era,” Jenkins wrote in 2014: Under this “uninspiring president,” the country “accomplished a revolution that seems almost impossible… deregulating large swaths of its transportation and energy industries while putting decades-old federal agencies to extinction.” Unlike most “revolutions,” Carter’s actually benefited the masses, in the form of radically cheaper shipping costs and affordable air travel for the general public. In 1965, fewer than 20 percent of Americans had ever flown in a plane; by the turn of the century, fewer than 20 percent hadn’t and 40 percent or more traveled by plane at least once a year. It’s impossible to imagine the rollicking economy of the ’80s and ’90s without his achievements.

Normalcy at Home

High prices and economic stagnation weren’t the only causes of America’s bicentennial malaise. Throughout the ’70s, Americans had been learning unsettling truths about crimes their government had committed against them in the name of national security. A 1971 break-in at a Pennsylvania FBI office exposed the agency’s “COINTELPRO” program of illegal wiretaps, burglaries, and domestic “black ops” against dissident groups at home. Shortly thereafter, former Defense Department analyst Daniel Ellsberg began leaking the Pentagon Papers, a classified history of the Vietnam War, that made clear that the country had been lied into a war that its leaders had long since concluded we couldn’t win. Then, in 1975 and ’76, a select Senate committee chaired by Idaho Democrat Frank Church uncovered outrages such as the CIA’s attempts to get the Mafia to assassinate Fidel Castro, National Security Agency spying at home, and the FBI’s effort to blackmail Martin Luther King Jr. into suicide.

In an era in which Americans were beginning to think of their intelligence agencies as officially sanctioned criminal conspiracies, Jimmy Carter imposed new limits on domestic spying and, on his first day in office, closed the book on a hideous war by pardoning draft evaders. Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater called the Vietnam amnesty “the most disgraceful thing a president has ever done”—worse than the Trail of Tears or Japanese internment, apparently. But if Ford could give Nixon a pass in the name of “domestic tranquility,” then surely some clemency was due to young Americans who simply didn’t want to kill and die in a war their betters knew to be a lost cause. (To his credit, Carter used the pardon power liberally, issuing 534 during his single term—more than any president since, including two-termers Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama.)

In May 1977, while the country was mesmerized by the Frost-Nixon interviews, Carter held a press conference pushing what he’d eventually sign into law as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. It made for an instructive comparison, a Washington Post editorial noted at the time: on one side, a disgraced former president insisting that “when the president does it, that means it is not illegal,” and on the other, “Jimmy Carter in the Rose Garden with Attorney General Griffin Bell…unveiling a bill that declares that, even in the most sensitive areas of national-security intelligence gathering, the President—like all other officials—shall be governed by law.”

The Carter record on civil liberties provides stark contrasts with other presidents as well: Despite Obama’s campaign-trail lip service to the notion that “nobody is above the law,” his administration didn’t prosecute anyone for torture, save a lone leaker who revealed details about the program. The Carter Justice Department prosecuted several top FBI officials, including the former acting director of the agency, for ordering illegal wiretaps and break-ins under COINTELPRO.

And speaking of disreputable presidential pardons: After their convictions, two of those officials got a pass from Reagan early in his first term. Reagan referenced Carter’s Vietnam amnesty in his statement accompanying the pardons: “America was generous to those who refused to serve their country….We can be no less generous to two men who acted on high principle to bring an end to the terrorism that was threatening this nation.” (“I certainly owe the Gipper one,” chirped one of the beneficiaries.)

Our Last ‘Peace President’

In 2014, when an interviewer read him a Carter-bashing quote from then–Arizona Sen. John McCain, the former president bristled: “That’s a compliment to be coming from a warmonger.” He went on, with a characteristic dose of self-serving exaggeration, to claim that under his presidency, “we never dropped a bomb, never fired a missile, we never shot a bullet.”

That assessment glosses over Carter’s late-term hawkishness, when he orchestrated a massive military buildup and armed the Afghan mujahideen. It also ignores his desperate and ill-conceived hostage rescue attempt in 1980, where but for a couple of balky helicopters he could have had us in a shooting war with Iran. After spending the night in the mountains outside of Tehran, a 118-man assault team was supposed to barrel their way into the embassy compound, rescue the hostages, and then fight their way to a nearby soccer stadium for extraction. In a riveting account of the debacle published in 2006, journalist Mark Bowden quoted a Delta Force operator who summed it up pithily: “The only difference between this and the Alamo is that Davy Crockett didn’t have to fight his way in.”

The mission failed during the “easy” part, with three of eight helicopters malfunctioning by the time they made it to the rendezvous point; had it gone forward, the whole operation would have looked like the Bay of Pigs meets Black Hawk Down.

In that episode, Carter nearly abandoned all the admirable restraint he’d shown before. And yet, among post–World War II commanders in chief, who else so reliably treated the use of force as a last resort? In 2002, he won the Nobel Peace Prize, an honor three other presidents have also received: Teddy Roosevelt, who stole the Panama Canal 75 years before Jimmy Carter gave it back; Woodrow Wilson, who dragged us into World War I after being reelected on the slogan “He kept us out of war”; and Barack Obama, who by the time he hit the dais at Oslo had already launched more drone strikes than George W. Bush carried out during two full terms. Of the four, only James Earl Carter could be said to have earned it.

On ‘Presidential Greatness’

When it comes to weighing up presidential legacies, Jimmy Carter’s frugality with American blood and treasure ought to count heavily in his favor. So why is he almost universally viewed as one of history’s losers?

One possible culprit is a trick of memory that Daniel Kahneman, the pioneering cognitive psychologist and 2012 Nobel Laureate in economics, has dubbed the “peak-end rule.” When we try to recall just how bad something was, “the worst part of the experience and the amount of pain just before the episode ends are weighted heavily in the final impression.” One of Kahneman’s key studies testing this hypothesis gave colonoscopy patients hand-held devices that let them record their level of discomfort in real time. It turned out that they remembered the probing as worse than it was on average if it hurt a lot at its peak and at the very end.

At the peak of pain, the Carter experience was pretty bad. The so-called misery index—the sum of the inflation and unemployment rates—hit 22 percent in June 1980 as the election loomed.

And, oh God, the end: In his last year, the guy just couldn’t win for losing. During his acceptance speech at the 1980 Democratic Convention, after Kennedy’s rousing “dream will never die” stemwinder, Carter’s teleprompter broke, he accidentally called the recently deceased former vice president “Hubert Horatio Hornblower,” and even the balloon drop failed. A week before the election, in their lone debate, Reagan pounded Carter on the misery index and Carter stumbled again, burbling in his closing statement that he wanted “to thank the people of Cleveland and Ohio for being such hospitable hosts during these last few hours in my life.” In the last hours of his presidency, Carter spent two sleepless nights overseeing negotiations with Iran, only to have the hostages released moments after Reagan’s inauguration, with the country watching on split screen as the prisoners got ready to come home.

As with colonoscopies, so too with presidencies: “Last impressions may be lasting impressions.” At its worst, and at the end, Carter’s presidency was painful enough to obscure the progress made. We couldn’t appreciate that overall, the procedure went pretty smoothly and to our benefit.

Yet something worse than cognitive bias seems to afflict the scholars who rank presidents and appraise their legacies. Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who helped popularize the presidential rankings game, wrote that “great presidents possess, or are possessed by, a vision of an ideal America. Their passion, as they grasp the helm, is to set the ship of state on the right course toward the port they seek.”

It helps if they cause a lot of turmoil along the way. Presidential rankers consistently award high marks for regime change abroad and at home—favoring “transformational presidents” who “leave the office stronger than they found it.” It’s a perverse metric, unless you think the executive branch can never have too much power. Nonetheless, the scholarly bias in favor of presidential activism puts Jimmy Carter, with his modest goals and mostly harmless errors, 15 places behind the monstrous Wilson in a 2018 survey of American Political Science Association presidential scholars.

More disturbing still, the rankers give bellicose commanders in chief a “combat bonus.” In a 2012 study, David Henderson and Zachary Gochenour found a strong positive correlation between the number of Americans killed in battle during a president’s term(s) and his place in such standings: “Military deaths as a percentage of population,” they concluded, are “a major determinant of greatness in the eyes of historians.”

By that standard, it’s to Carter’s credit that he’s never ranked among the “great presidents.” His “passionless presidency” did comparatively little harm and a considerable measure of good. We could do worse. We usually do.

The post RIP Jimmy Carter, the ‘Passionless’ President appeared first on Reason.com.