Some of My Big 2025 Questions

In keeping with Capitolism tradition, this first newsletter of 2025 will examine some of my big, open questions for the coming year—questions that could have major implications for the U.S. and global economies but don’t yet have a reasonably clear outcome. My previous questions from 2023 and 2024 hold up pretty well, I think, and hopefully these will too. If not, they’ll still give you an idea of some of the things I’ll be watching and writing about this year.

,

For today’s discussion, I’ll omit tariffs and U.S. trade policy because we already went over most of that in November, and little has changed in the weeks since. (I’m also tired of talking about tariffs!) We’ll surely dig into that again soon, but for today you can read on with the comfort of knowing that trade wonkery will be mentioned only in passing.

,

,

And with that, let’s get started.

Will the U.S. Productivity Boomlet Fizzle?

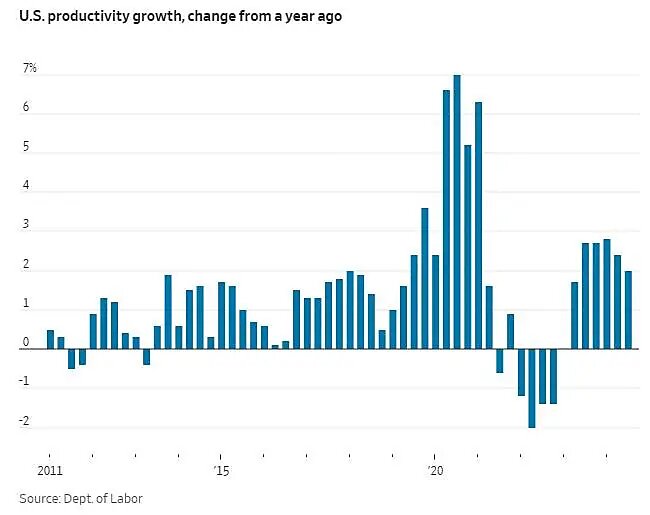

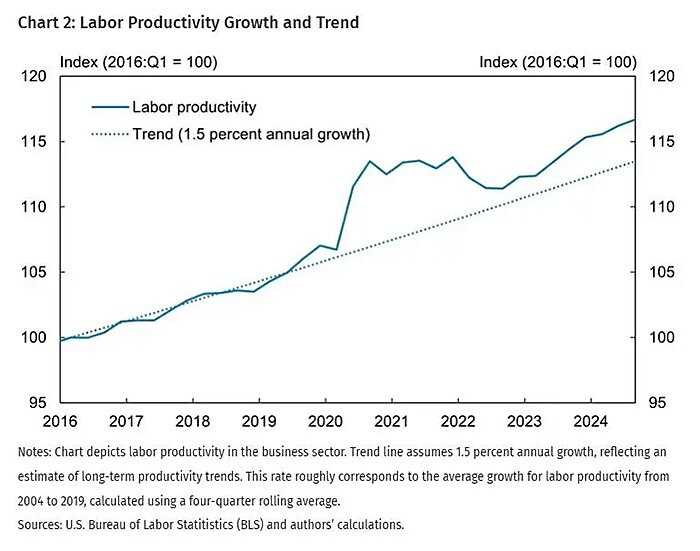

As we discussed last year, one of the reasons the U.S. economy has zoomed ahead of its peers is a surprising surge in productivity—making more stuff with the same number of inputs (most notably workers), thus fueling growth and wages while tempering inflation.

,

,

Early in the pandemic, some of this surge was an illusion—people in low-productivity services jobs were furloughed or fired, while higher-productivity workers kept at it, thus masking whether the “increase” was real or driven by pandemic-biased data. Since then, however, U.S. productivity has continued to exceed the prepandemic trend:

,

,

Economists attribute the surge to a combination of several factors. For example, a tight labor market prodded U.S. companies to embrace automation and other labor-saving technologies, while also helping workers sort into higher productivity (and higher paying) jobs. COVID-era disruptions caused a surge in new business formation, which can also boost innovation and efficiency. Remote work, artificial intelligence, and immigration also played a role, helping workers get more done in less time. And, as we’ve discussed, underlying all this dynamism is the United States relatively open and fluid economy (huzzah).

The big question for 2025 is, as the Kansas City Fed recently explained, “whether the recent productivity surge represents a sustained shift to a higher growth trajectory or a temporary boost driven by cyclical factors and pandemic-induced changes.” Job churn (quits, hires, etc), for example, has retreated from its postpandemic highs; remote work and business formation are still elevated but might further regress; and questions remain as to how much more each of these factors will contribute to future productivity growth. Along with structural factors like educational attainment and an aging society, productivity could return to its slower, prepandemic normal if the low-hanging fruit has now been picked.

On the other hand, demographics and slowing immigration (more on this below) mean that the labor market should remain tight, thus enabling more job-switching and upskilling. Artificial intelligence will also surely continue to improve (though it still hasn’t destroyed all the jobs and/or the human race). Overall, my guess is that the good will outweigh the bad, there’s still fruit to be picked, and that we’ll continue to benefit from the recent productivity surge. That’d be good news for the U.S. economy and workers, but it’s just a hunch.

Will American Manufacturing (and ‘Bidenomics’) Finally Boom?

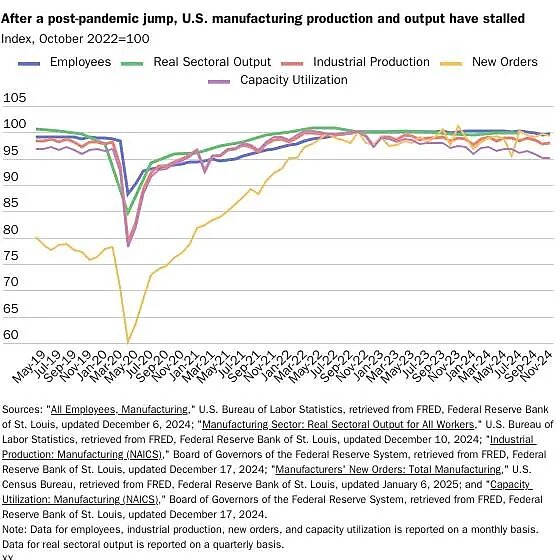

As we discussed last year, reports of an industrial policy-driven U.S. manufacturing “boom” were at best premature, reflecting a significant increase in domestic manufacturing construction spending but ignoring that the actual U.S. manufacturing sector was—by all sorts of metrics—struggling mightily. Those struggles persisted through the fall, with the latest public figures and private surveys continuing to show a sector in long-term contraction. Recently, some Bidenomics cheerleaders have started having second thoughts.

,

,

There are, however, some recent signs of improvement for U.S. manufacturing, and more gains could be on the way if the Federal Reserve continues to cut interest rates, Trump tax and deregulatory tailwinds emerge, and several high-profile U.S. industrial policy projects finally come online. Most notable in this last group may be TSMC’s first advanced semiconductor plant in Arizona, which should begin commercial production of (not-quite-bleeding-edge) 4‑nanometer chips in the second-half of the year. This phase, it must be noted, is relatively small and started before the CHIPS Act became law, but its success would be a tailwind for more and bigger stuff down the road. Intel’s big bet on advanced chipmaking—so-called “18A”—is also expected later this year, and several big Inflation Reduction Act-funded projects (e.g., these Hyundai EV and battery plants) are either just now operational or soon will be.

On the other hand, a few new discrete successes are not the same thing as a sector-wide revival, and there are plenty of huge questions about a lot of U.S. industrial policy projects (more on this later). Manufacturing also could still struggle in the face of new tariffs and tariff-related uncertainty, global instability, and continued difficulties in filling open jobs. On this last point, consider a recent Wall Street Journal piece noting that, even as other blue collar sectors have fully recovered from the pandemic and the labor market has softened a bit, American manufacturers still can’t find workers:

,

For most of this year, the gap each month between manufacturing job openings and hirings has hovered at about 100,000 positions. More than 60% of employers in a recent survey by the National Association of Manufacturers said attracting and retaining talent is a top concern. The trade group forecasts the sector will need to fill 3.8 million roles over the next decade because of retirees leaving the industry and growing manufacturing demand.

,

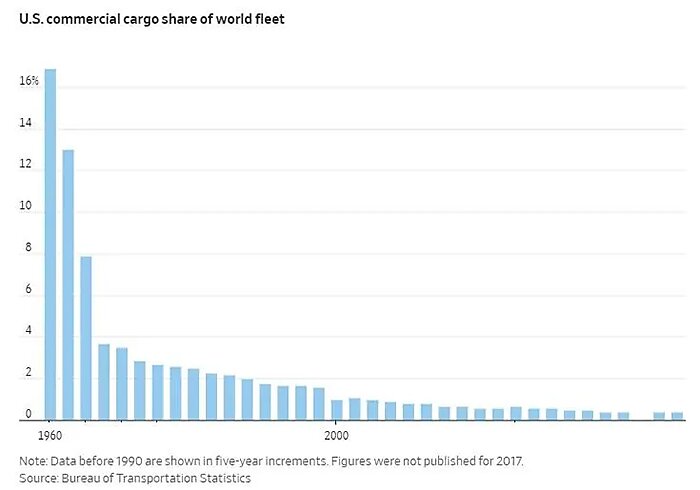

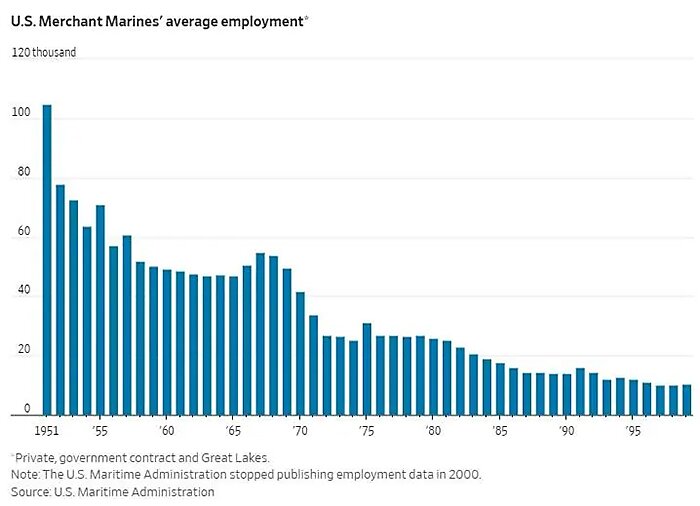

Elsewhere, the Journal’s Greg Ip notes that the “hidden threat” to national security-related manufacturing—in his case, shipbuilding—is “not enough workers,” thanks in part to the disappearance of significant wage premiums for the industry and disinterest among younger job entrants. As one U.S. manufacturer put it elsewhere, “You can make almost anything here, as long as it doesn’t require lots of labor”—and, despite being relatively productive, U.S. factories still need lots of humans. Future immigration restrictions will likely exacerbate this issue, given the dearth of available native-born workers. Consider, for example, that about half of the workforce at that much-ballyhooed TSMC plant in Arizona is Taiwanese—owed in part to special treatment the company secured from the Trump administration years ago. Will other manufacturers be so lucky?

Will There Be a Broader Labor Market Shock?

Other sectors face similar workforce challenges because of the broader demographic and immigration trends we’ve already discussed. In tech, for example, “there were twice as many job openings as unemployed workers in the ‘professional and business services’ sector, which includes most tech fields”—hence why so many companies depend on and benefit from the (needlessly controversial) H‑1B visa program. Many of these industries can mitigate labor challenges with remote work, offshoring (from other states and other countries), and technology like AI. Physical activities, on the other hand—manufacturing, construction, farm work, in-person services, etc.—have fewer options in this regard. And, as Barclays’ Ajay Rajadhyaksha just detailed, U.S. firms could be in for a rude awakening this year as native-born workers continue to retire and immigration continues to retreat from Biden-era highs:

,

It takes around six to nine months for new immigrants to officially hit the workforce. Which means that president Biden’s [June 2024 “Remain in Mexico”] decision should show up in shrinking labour supply soon. We estimate this action alone will knock off 750k from labour supply next year. Moreover, when president-elect Trump takes over, he’s likely to put in place other measures to slow down immigration, as he has promised. This means that US labour supply from immigration will rapidly go back to the averages of the Trump term — around half a million new workers a year. That’s a massive drop-off from the 2mn-plus of the last three years.

,

Combine reduced immigration with U.S. demographics (“the native-born population is growing below replacement rates”), already-high levels of labor force participation, and post-COVID wealth keeping retirees on the sidelines, and, per Rajadhyaksha, “It’s clear that a sharp shrinkage in immigrant labour supply will bite” the U.S. economy. If so, that could mean more persistent inflationary pressures (and challenges for the Federal Reserve), lower growth, thwarted industrial policy, and other problems. So, it’ll definitely be something to watch.

Will the Trump Coalition Hold (and Will Congress Pass Anything)?

I don’t want to venture too far into Jonah’s rank punditry lane, but a big factor for U.S. economic policy next year will be political: whether and to what extent the wildly diverse “Trump coalition” of MAGA-hat populists, tech bros, paleolibertarians, and more traditional Republicans (Reaganite and Buchananite) will avoid shivving each other long enough to implement significant economic policy.

We saw this schism erupt—somewhat hilariously—over the holiday break, as a few gutter-origin shots at a pro-immigration Trump nominee quickly devolved into a multiday online war over H‑1B visas that featured, and I kid you not, Vivek Ramaswamy (erroneously!) tweeting about Saved by the Bell and Elon Musk then yelling “‘F*** Yourself in the Face” at a random tweeter/customer late Friday night after Christmas. The fracas eventually died down, but—as David Brooks rightly noted at the time—the rift is not a one-off thing but instead reflects a fundamental divide between the Trump coalition’s pro-market dynamists and its market-skeptical reactionaries. Brooks opines that the tensions here will affect “economic regulation, trade, technology policy, labor policy, housing policy and so on.” And I tend to agree, especially since the movement’s leader has so few strong ideological or procedural views (beyond “Trump win” and “tariffs great,” of course).

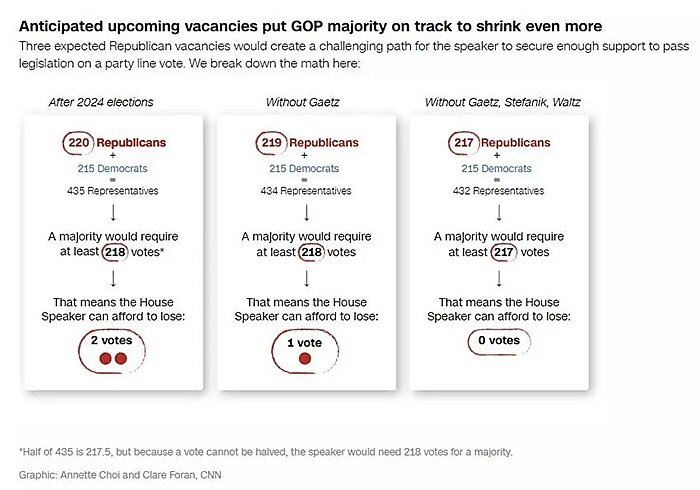

The schism could affect the legislative branches too, seeing as Republicans’ House majority is the narrowest in nearly a century. Until pending vacancies are filled, in fact, “House Republicans would not be able to afford a single defection to pass legislation along party lines.” What could go wrong?!

,

,

With major fights coming soon over the expiring Trump tax cuts and the debt ceiling (which the Economic Policy Innovation Center projects will be hit in June), any serious divides among the Trump coalition could make legislating not just difficult, but downright impossible. Heck, even minor ones – like the expiring cap on state and local tax deductions (“SALT”) that a handful of Republicans in high-cost places campaigned on – could derail legislative momentum for even the tip-toppiest Trump priorities. Throw in very real market concerns about tariffs and U.S. debt levels, as well as baked-in expectations that taxes get cut, and the dysfunction could affect the real economy—and our 401(k)s. Republican leadership and Team Trump seem to be working overtime to preempt these problems, but it’s only January and these things tend to take on a life of their own (as the H‑1B comedy shows). How the GOP navigates the tensions thus promises to be a big economic storyline, whether we – and they – like it or not.

What Now, China?

Last year, I wondered about the future of China’s teetering economy and closed with this:

,

Instead of reversing course and reembracing markets, [Chinese President Xi Jinping] is reportedly doubling down on the Marxism and industrial policy. … Both carry big risks: The former could further depress the Chinese citizenry, foreign investors, and the economy more broadly; the latter can’t fully offset domestic real estate, consumption, and other economic problems, but it can ignite even more trade conflicts as subsidized overcapacity reaches foreign markets and angers local politicians, many of whom are running for reelection in 2024.

,

We now know that this is basically what happened in 2024: China’s longstanding economic headwinds—demographics, productivity, debt, social/political control, etc.—combined with continued weakness in local property markets, depressed consumer sentiment, policy-driven industrial overcapacity, investor doubt, and heightened trade tensions to keep China’s economy in the doldrums. (Hooray, central planning!) The Japan “lost decade” parallels have thus gained steam:

,

China’s economy remains trapped in a deflationary quagmire, with producer prices falling for 26 consecutive months, dropping 2.5% year-over-year in November. Consumer inflation is barely hovering above zero, with prices inching up just 0.2% in the same period.

That draws an uncomfortable parallel to Japan, which was mired in decades of deflation until forceful stimulus finally pulled it out in recent years. Indeed, China’s 30-year bond yield has now sunk below that of Japan, which stands at 2.3%. Similar to Japan’s property and stock bubble bursting in the early 1990s, China’s current predicament came after the implosion of its housing bubble around 2021.

,

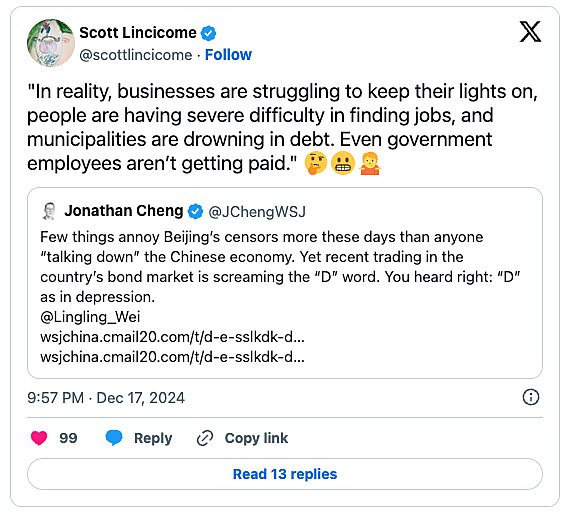

As this Journal article notes, the “impending trade war with the U.S. in the second Trump administration may further worsen the situation.” And reality on the ground in China may be worse than the (government-manipulated) statistics lead on:

,

,

According to the Rhodium Group and other economists, in fact, China’s actual economic growth (GDP) last year may have been just half the official 5 percent target the country just-so-happened to hit on the nose. The Journal reported today that Xi has muzzled yet another Chinese economist who questioned the government’s numbers and its economic recovery plans. And I’ve lost count of the number of China hands, investors, and journalists who returned from visiting the country last year and lamented the clear shift in public sentiment today (pessimism) versus a decade ago (optimism), especially among young people and entrepreneurs.

As I said last year, none of this means the country is on the verge of collapse or anything like that, and I stand by that again today. China is making real progress in certain tech-heavy areas and still boasts a massive economy and talented, hardworking labor force. But it’s economic situation remains delicate and opaque; central planning doesn’t exactly have a sterling record for long-term success; and the warning signs today are almost everywhere. Given the implications for geopolitics, the U.S. and global economies (and U.S. economic policy), Xi’s and the CCP’s ability to maintain social control, and other big issues, the near-term future of the world’s second largest economy remains a top storyline.

Will Bad Pandemic Trends Continue Their Welcome Reversal?

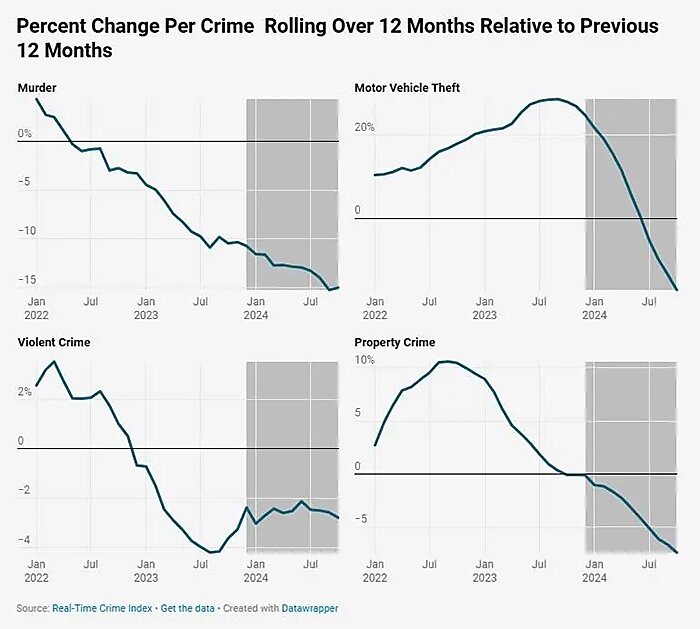

One of the pandemic’s worst effects was that it fueled many bad social trends in the United States, but—as psychology professor and eternal optimist Steven Pinker wrote in October—we seemed to have turned a corner in the last two years on various economic and social fronts. Homicide rates, for example, are now back to prepandemic levels (and way below those from decades ago), and recent trends have been improving for other types of crime too:

,

,

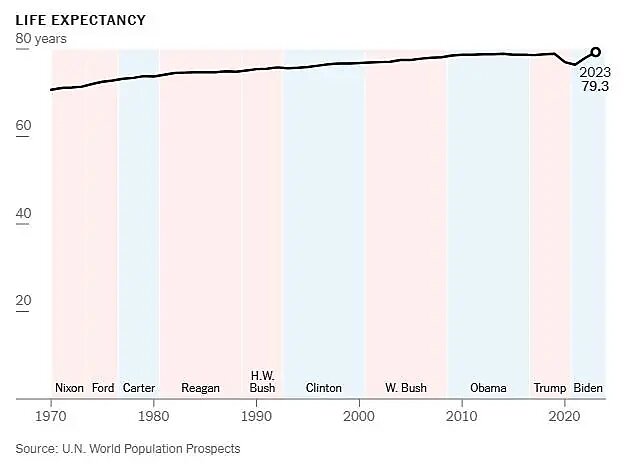

Pinker also shows that life expectancy has rebounded, and it’s projected to have improved further in 2024:

,

,

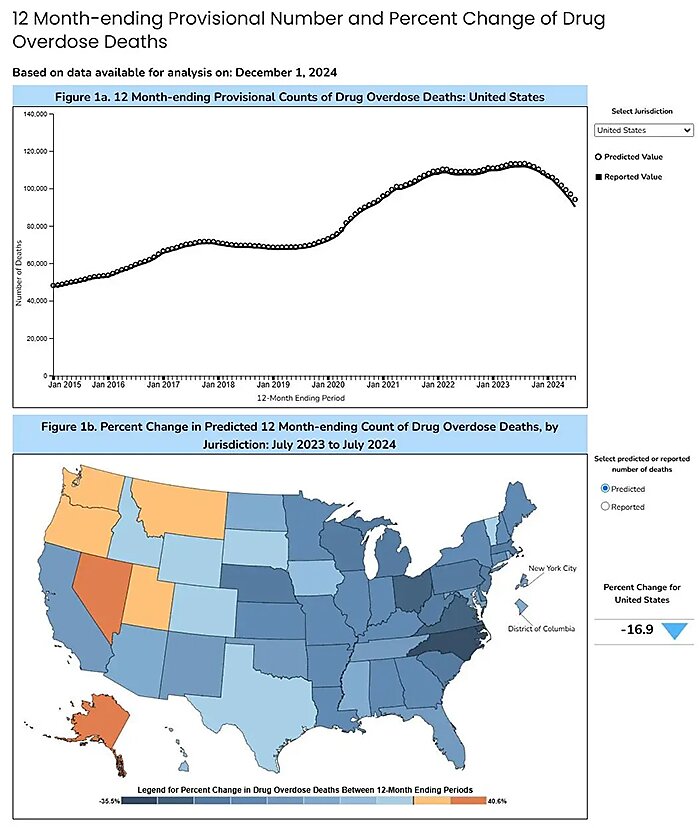

Elsewhere, we see that drug overdoses also keep trending in the right direction and are almost back to prepandemic levels nationwide (with even bigger drops in certain states):

,

,

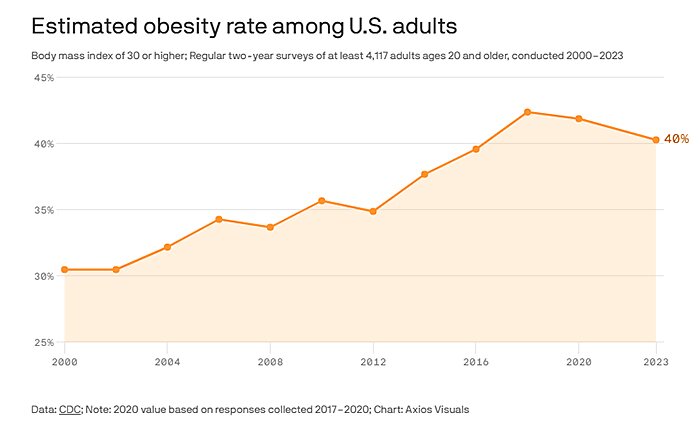

Obesity also seems to have turned a corner:

,

,

And, per Cato’s new Human Freedom Index, the United States and the world saw modest rebounds in 2022 from their (depressing) pandemic-era declines.

We still have a ways to go in many cases, but the trends here are undeniably positive—so far. Whether they continue, thanks to a general, post-pandemic recovery, better policy, or new medical marvels like GLP‑1 drugs, will certainly be something to follow—not only because further improvement would be good for humanity, but also because it’d be another strike against the populist, anticapitalist pessimism that’s all the rage today.

Fingers crossed.

Chart(s) of the Week

,

,

,

,

,

,