Sunlight Is the Best Accelerant

Why does America struggle to quickly deliver the weapons it sells to foreign countries via the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) process? As the primary U.S. government tool for providing weapons to foreign countries, FMS typically entails new production of military equipment. And while Direct Commercial Sales and Presidential Drawdown Authority can get weapons to foreign countries faster, they involve relatively less technologically complex capabilities and require congressional authorization to transfer large quantities of weapons, respectively.1 Given the bureaucratic and manufacturing processes involved, the FMS process has never been a tool for rapid delivery; however, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, a recent surge of new FMS cases, and abnormally long wait times for FMS deliveries to Taiwan have drawn greater policymaker attention and concern.

,

,

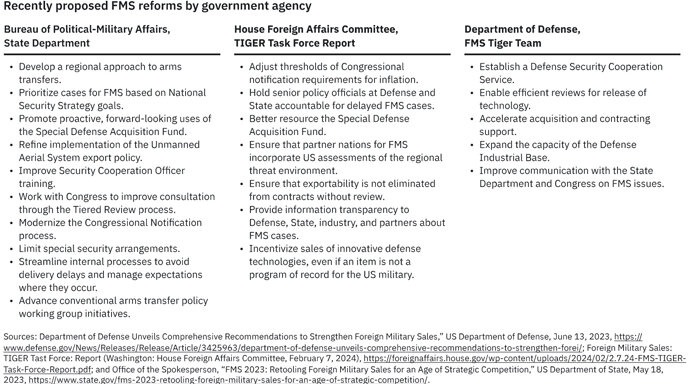

Since May 2023, the three primary stakeholders in the FMS process—the State Department, Department of Defense, and Congress—have proposed reforms aimed at streamlining the security assistance bureaucracy.2 These efforts may be fruitful, but the history of FMS reform is not promising, and the current effort focuses heavily on only one of many potential sources of delays—the bureaucracy.3 Without greater transparency, it will be impossible for policymakers and nongovernment analysts alike to identify the source of these delays or make effective changes.

,

,

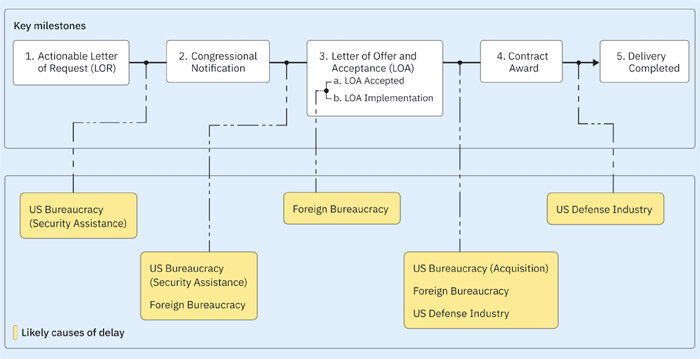

In addition to federal agencies, foreign government bureaucracies and the U.S. defense industry can also contribute to long wait times. Each comes into play at different times, but large gaps between the milestones mentioned above can reveal which is most likely at fault. In the current system, however, a general opacity around those milestones makes it difficult to accurately diagnose the problem.

Fixing delayed arms deliveries requires more publicly accessible information about the timing of key milestones in the FMS process. Simply knowing five dates—those of the actionable Letter of Request (LOR), Congressional notification, Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA) signature, contract award, and final delivery—would allow observers to identify the sources of delay.

Gordian Knot

The problem of data availability in FMS delays was the theme of an August 2024 RAND Corporation report on FMS reform. As the RAND researchers write, “Quantifying FMS delays proved too difficult to pursue…Due to the presence of some gaps or inconsistencies in the case development data we received from DSCA, we were unable to confidently interpret the results of the quantitative analysis we conducted and to independently quantify the extent of delays in the FMS case development phase.”4 Even the U.S. government agencies responsible for arms sales and security assistance struggle with data availability. As stated elsewhere in the RAND report, “the FMS community lacks a coordinated approach to data governance…A [Department of Defense] policy-level official described this situation: ‘All the different services use different systems, and the data doesn’t communicate.’”5

Getting an accurate picture of the causes of arms sale delays is therefore difficult not only for nongovernment analysts, but also for the agencies responsible for implementing FMS cases, because data is scattered and stove-piped. Existing efforts to reform the FMS process are welcome, but they are almost exclusively focused on addressing U.S. bureaucratic issues and not other potential sources of delays. A handful of recommendations mention the U.S. defense industrial base or foreign governments, but the vast majority are focused on changing the U.S. government approach to FMS. To be clear, many of these changes could reduce delays emanating from the U.S. bureaucracy. However, as the Taiwan case study below shows, other sources of delay can have equal or even larger impact than U.S. bureaucratic inefficiencies. and these sources are largely unaffected by recently proposed reforms. Fixing the problems with the U.S. security assistance bureaucracy is necessary but not sufficient.

Case Study: Taiwan Arms Backlog

Since November 2023, I have maintained a dataset tracking the U.S. arms sale backlog to Taiwan.6 As of September 2024, this backlog was assessed to be $20.5 billion. Of the five key FMS milestones mentioned earlier, only the date of Congressional notification is readily available. Accurate information about other steps in the process, including final delivery, is not easily publicly accessible: most are either buried in obscure sources or simply not publicly available, even when unclassified. The Defense Security Assistance Management System (DSAMS), the system used by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) to process FMS cases, contains only unclassified information, and classifying LOAs, while possible, is “strongly discouraged.”7 However, DSCA does not publicly release information about LOAs. Defense industry and foreign governments will sometimes announce deliveries of major weapons systems, but delivery of less significant capabilities often fly under the radar.8

Byzantine U.S. bureaucratic practices have understandably been the primary target of FMS reform efforts, but several cases from the Taiwan backlog show how delays can come from other sources. In October 2023, Reps. Mike Gallagher (R‑WI) and Young Kim (R‑CA) sent a letter to the secretary of the Navy inquiring about delays in FMS cases for Harpoon anti-ship missiles and the SLAM-ER, a variant of the Harpoon used to attack ground targets.9 The letter states that a sale of 60 air-launched Harpoon missiles was notified to Congress in September 2022 and that Taiwan signed a LOA for the weapons in December 2022, a gap of three months. By comparison, there was a gap of over two years between Congressional notification of the SLAM-ER sale (October 2020) and Taiwan’s signature of a LOA (December 2022). For both sales, according to the letter, as of October 2023, the Navy had not issued requests for the defense industry to produce the missiles.10 The short gap between Congressional notification and LOA signature in the air-launched Harpoon case suggests that both the U.S. and Taiwanese bureaucracies quickly completed their tasks, while the long gap between the same milestones in the SLAM-ER case points to bureaucratic delays. For both cases, the long gap between LOA signature and a contract suggests that the U.S. defense industrial base or U.S. procurement agencies are slow.

Taiwan has also faced significant delays in deliveries of portable anti-air weapons. Taiwan is waiting for delivery of 500 Stinger missiles divided evenly across two FMS cases notified to Congress in December 2015 and July 2019.11 According to an October 2023 report from Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense (MND), there was a two-year gap between congressional notification and LOA signature for the 2015 sale for the navy.12 However, the MND had to re-sign the LOA in 2020 because the army also wanted to purchase Stingers and it took time to create a new FMS case. According to the MND’s report, the U.S. did not sign a production contract for the Stingers until September 2022, two years after the updated LOA signature and almost seven years after the initial congressional notification in December 2015.

The Taiwanese government is the major source of delay in the Stinger FMS cases. The MND report mentions that Taiwan did not budget for the Stinger purchase until 2017, almost two years after the congressional notification milestone. This gap, plus Taiwan’s purchase of additional Stingers for its army shortly after signing the initial LOA further lengthened the delay in getting a production contract signed. The MND has expressed frustration with the production timeline, but all 500 Stingers should arrive in Taiwan no later than 2025, just three years after the contract was signed.13 In other words, the primary culprit for Taiwan’s Stinger woes is the Taiwanese government itself.

The cases above provide valuable insight into how different delay sources affect different FMS cases, but they also illustrate the problem of data availability in the arms sale process. Every mention of LOA signature dates found in my research has been either in letters from members of Congress to DOD officials or in Taiwanese defense budget documents not published in English. While it may be technically possible for analysts to put together a comprehensive picture of FMS delays, the lack of readily available data makes such an analysis time consuming and prone to inaccuracy.

What The Five Milestones Reveal

Fixing the data availability problem by publicizing the dates of five key milestones in the FMS process—actionable LOR, Congressional notification, LOA signature, initial contract award, and final delivery—will make other FMS reforms more targeted and therefore more likely to be effective. The top half of Figure 1 shows the five milestones as a flowchart (with the first at the left and the last at right). The bottom half indicates likely delay sources.

,

,

Milestone 1: Actionable Letter of Request (LOR)

The FMS process formally begins with a foreign country submitting a Letter of Request (LOR) to purchase U.S. weapons or military services to an implementing agency in DOD or, in rare cases, the U.S. intelligence community.14 There are various types and statuses of LORs, and it can take time for the implementing agency and the foreign government to complete the back-and-forth process that makes a LOR the foundation of an FMS case. The most important type of LOR for determining where delays exist in the FMS process is an actionable LOR.15 Once an LOR has the necessary information to be labeled actionable, the implementing agency can proceed with developing the FMS case.16

Milestone 1 is the date when the implementing agency enters “LOR Actionable” into DSAMS.17 Per the Electronic Security Assistance Management Manual, “An ‘LOR Actionable Date’ must be entered into DSAMS before case development activities may begin for Category C documents.”18 All FMS cases that must go through Congressional notification, including all that involve significant military capabilities or dollar amounts, are considered Category C.19

Milestone 2: Congressional Notification

Section 36(b) of the Arms Export Control Act requires that Congress be notified of certain FMS cases before a LOA can be offered to the foreign purchaser. Congress has an opportunity to block the FMS case by passing a joint resolution of disapproval but, since the president could veto it, Congress rarely passes such legislation and has never successfully blocked an arms sale.20 All FMS cases above a certain dollar threshold and amendments to old FMS cases that would increase the total case value above the thresholds must be notified to Congress. These thresholds are $25 million, $100 million, and $300 million for major defense equipment, defense articles or services, and design and construction services, respectively, for NATO countries, South Korea, Australia, Japan, Israel, and New Zealand. For all other countries, these thresholds are $14 million, $50 million, and $200 million.21

Congressional notification is already the most visible part of the FMS process. It is the only one of the five milestones that is readily available and reliably reported. DSCA publishes press releases with information about all new Congressional notifications on its website, and arms sale notifications are posted in the publicly available Congressional Record.22 Amendments to previously notified FMS cases—such as the December 2022 sale of Patriot interceptor missiles that was tacked onto a 2010 sale of Patriot launchers—are not posted on DSCA’s website but are in the Congressional Record.23 Notifications include a description of the items being sold and a cost estimate, but both quantities of equipment and prices can change as the FMS case advances to later milestones.

A long delay between an actionable LOR and Congressional notification of an FMS case would be primarily the fault of the U.S. government, namely the security assistance bureaucracy in DOD and the State Department.24 The U.S. security assistance bureaucracy is responsible for preparing all the necessary documentation for Congressional notification. A long period of time between an actionable LOR (milestone 1) and Congressional notification (milestone 2) suggests that the U.S. bureaucracy is taking longer than anticipated to complete its work. The foreign government purchaser may be at some fault at this stage of the process since they are involved with submitting the LOR, but for a LOR to be marked actionable most of the heavy lifting for the foreign government should be complete.

Milestone 3: Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA) Signature

The LOA is the legal instrument that the U.S. government uses to sell weapons and military services as part of the FMS process. A LOA contains an itemized list of the equipment being sold as well as cost estimates and a payment schedule.25 A signed LOA is an important milestone in the FMS process because the U.S. government cannot enter a contract with defense industry to produce equipment until the LOA is signed.26 Additionally, the U.S. government cannot offer an LOA for signature until the FMS case clears the Congressional notification milestone. Both the U.S. security assistance bureaucracy and the foreign government purchasing the equipment are involved in preparing a LOA for signature, and representatives from both the U.S. government and foreign government must sign the final LOA to advance the FMS case past this milestone.

Unlike the four other milestones, LOA signature contains two subcategories: “LOA Accepted” and “LOA Implemented.”27 An LOA is considered accepted when the foreign government signs the document and implemented when the foreign government makes their initial deposit to pay for the FMS case. A long gap between Congressional notification and “LOA Accepted” could be due to either U.S. or foreign government bureaucracies. However, a delay between “LOA Accepted” and “LOA Implemented” is solely the fault of the foreign government purchaser.

A delay between Congressional notification and LOA signature stems from the U.S. security assistance bureaucracy and/or the foreign government purchaser’s bureaucracy. Congress has either 15 days or 30 days, based on the purchasing country, after notification to review the FMS case and vote to block it.28 The U.S. security assistance bureaucracy should have most of its work on the LOA completed before Congressional notification, so the document can be offered to the purchaser for signature shortly after the review period is over, but there is no guarantee that this is the case. Congressional notification requires the security assistance bureaucracy to submit a package of documents that is extensive but does not perfectly overlap with the reviews and documentation involved in creating a finalized LOA.29

Even if the U.S. security assistance bureaucracy moves quickly and has a LOA ready for signature, the foreign government purchaser may have their own unique policy processes that delay their acceptance of a LOA. For example, according to a Taiwan MND press release “…all foreign military purchases must be approved by the Legislative Yuan with budget appropriation before signing a Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA).”30 Other purchasers with more flexible approval and budgeting processes may be able to sign a LOA as soon as it is offered.

While foreign bureaucracy shares culpability with U.S. security assistance bureaucracy for a delay in LOA acceptance, a gap between acceptance and implementation is solely the fault of the purchaser. The LOA is considered implemented after the foreign purchaser has signed the document and made an initial deposit of funds to pay for the FMS case. The initial deposit is important because the implementing agency cannot begin negotiating production contracts with defense industry or taking other steps to procure equipment or services until the deposit is received.31 The U.S. security assistance bureaucracy has completed all its major tasks by the time the LOA is accepted by the foreign purchaser. Any delay between LOA signature and the deposit of funds is therefore due solely to the purchasing government.

Milestone 4: Contract Award

The fourth milestone for identifying sources of delay in the FMS process is the date when a contract is awarded to defense industry to produce equipment or services. As explained in DSCA’s Foreign Customer Guide, “Under FMS, the U.S. Department of Defense procures defense articles and services for your country using the same acquisition process to procure for its own military needs…The contract will be between the U.S. [government] and the U.S. defense contractor…FMS customers are not legal participants in the procurement contract.”32 The foreign customer makes deposits with the U.S. government as stipulated in the LOA, and the Department of Defense uses those funds to pay the contractor.

The DOD publishes contract award announcements, including those that are paid for using FMS funds.33 This is a rare bright spot for data availability. However, these announcements frequently involve multiple FMS customers on the same contract with a single estimated end date, which makes it impossible to know the order in which the FMS customers will receive their equipment. Additionally, for some items in the Taiwan backlog, the completion date mentioned in the award announcement does not match information from MND about when weapons are supposed to be delivered.34 This could be due to post-delivery support activities but given the limited information in the award announcements it is impossible to say for sure.

The contract award date is an important milestone for two reasons. First, it marks a change in the U.S. government agencies that are responsible for delays, with the procurement bureaucracy replacing the security assistance bureaucracy. Acquisition officials and agencies are responsible for negotiating contracts to fulfill FMS cases, but they use different data systems and have different lines of authority than the agencies that construct and approve FMS cases.35 Even if the security assistance bureaucracy quickly clears all its milestones, foot dragging by the procurement bureaucracy could delay a contract award. Problems with timely procurement are a longstanding issue. Per an August 2024 RAND report, “In the words of one DSCA interviewee, [the office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment] and its predecessor ‘have really been dropping the ball for twenty years’ when it comes to working with the services and DSCA on developing a [Department of Defense]-wide acquisition information management platform that was compatible with security assistance data systems.”36

Second, the contract award is the first milestone where the U.S. defense industrial base becomes a potential source of delays. Before the contract award, the U.S. defense industry is not heavily involved in the FMS process. Contract negotiations between U.S. procurement agencies and defense industry could take longer than anticipated for a variety of reasons that could be the fault of either the government (budget delays, long review periods, etc.) or industry (labor shortfalls, limited production capacity, etc.).

The foreign purchaser could also be responsible for delays between LOA signature and contract award if it has problems meeting the payment schedule set forth in the LOA or if it decides to restructure its FMS case. However, the U.S. procurement bureaucracy and U.S. defense industry are the more likely sources of delay between these milestones.

Milestone 5: Delivery Completed

The fifth and final milestone is final delivery of equipment or services to the recipient country. Data on final delivery is spotty. Countries or the defense industry will sometimes make official announcements to draw attention to delivery of high-profile weapons such as fighter aircraft. For most FMS cases, however, it can be very difficult to discern when final delivery has occurred. Analysts could use the completion date on contract award announcements to get a rough sense of delivery, but using that date would not capture delays in delivery that crop up after the contract is first awarded, and contracts may include post-delivery support activities.

A delay between contract award and final delivery is solely the responsibility of the U.S. defense industry. The U.S. acquisition bureaucracy struggles with sharing information about production delays with other parts of security assistance bureaucracy, but at this stage in the process the acquisition bureaucracy is not responsible for those delays. Examples of weapon production issues that have delayed delivery to Taiwan include software problems in F‑16 aircraft, failed quality control tests for TOW-2B anti-tank missiles, and the need to re-start the SLAM-ER production line.37 Beyond Taiwan-specific issues, the U.S. defense industrial base faces systemic problems like worker shortages, limited production lines, and uncertainty about the defense budget.38 The U.S. defense industry is aware of these challenges and appears eager to fix them. In fact, in 2023 the National Defense Industry Association recommended that the U.S. government “implement a start-to-finish tracking system for FMS contracts to support U.S. allies and partners through the LOR, LOA, and acquisition process,” which is very similar to the milestones in this paper.39

Conclusion

Knowing the dates of the five key milestones can give analysts and policymakers a better sense of which stakeholders are causing delays in FMS cases. Unclassified information about all these dates already exists, but the data is spread over multiple information systems that do not automatically communicate with one another. Through the annual National Defense Authorization Act, Congress could pass a reporting requirement that forces the Department of Defense to provide the dates of the five milestones in a publicly accessible format. The information is out there, but without a forcing function to put it all in one place it will continue to be fragmented and hidden from scrutiny.

There is a legitimate concern that publishing information about FMS cases that have not been fully delivered, or those that are in the initial stages of negotiation could increase the risk of adversary action to dissuade or preempt an arms sale. This risk could be addressed by releasing the dates of the five key milestones for FMS cases that have already been delivered. The data for such cases would not be “real time” but it would still prove valuable for identifying delay sources. Additionally, the potential risks of disclosing the five key milestones dates must be weighed against the benefits of having a more accurate picture of FMS delays that can result in more targeted and effective policy reform.

As mentioned earlier, in the recent push to reform the FMS process the focus has been almost entirely on changing the U.S. security assistance bureaucracy. These institutions need reform, but focusing too narrowly on them could lead to policy changes that address only part of the problem. Greater transparency around the FMS process will make life better for all its stakeholders. The U.S. government will be able to better direct its reform efforts, foreign governments can get better insight into whether delays are unique or systemic, and the U.S. defense industrial base will get greater insight into what is coming down the pike. The need for reform is great and the data already exists. Sunlight is not only the best disinfectant, but also the best accelerant, and knowing the dates of these five FMS milestones can fix the problem of arms sale delays.